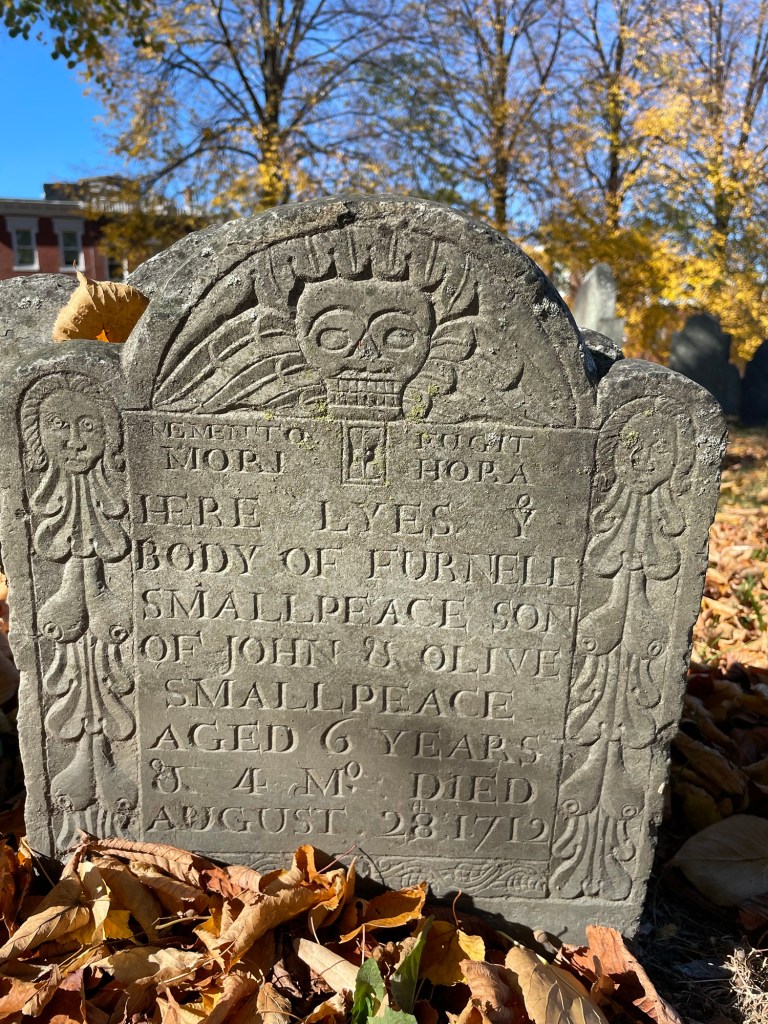

Happy Halloween! Welcome to Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, a historic cemetery nestled in Boston’s historic North End. Established in 1659, it served as a burial site for some of Boston’s earliest settlers and notable figures, including craftsmen, merchants, and members of the influential Mather family. Also burie here is abolitionist and leader in the free black community in Boston, Prince Hall. Originally called North Burying Ground, Copp’s Hill was the second place of interment on the Boston peninsula and was laid out in 1659. The area acquired its present name through its association with William Copp (1589-1670), a shoemaker and early settler who lived near today’s Prince Street; ironically, his stone is no longer standing.

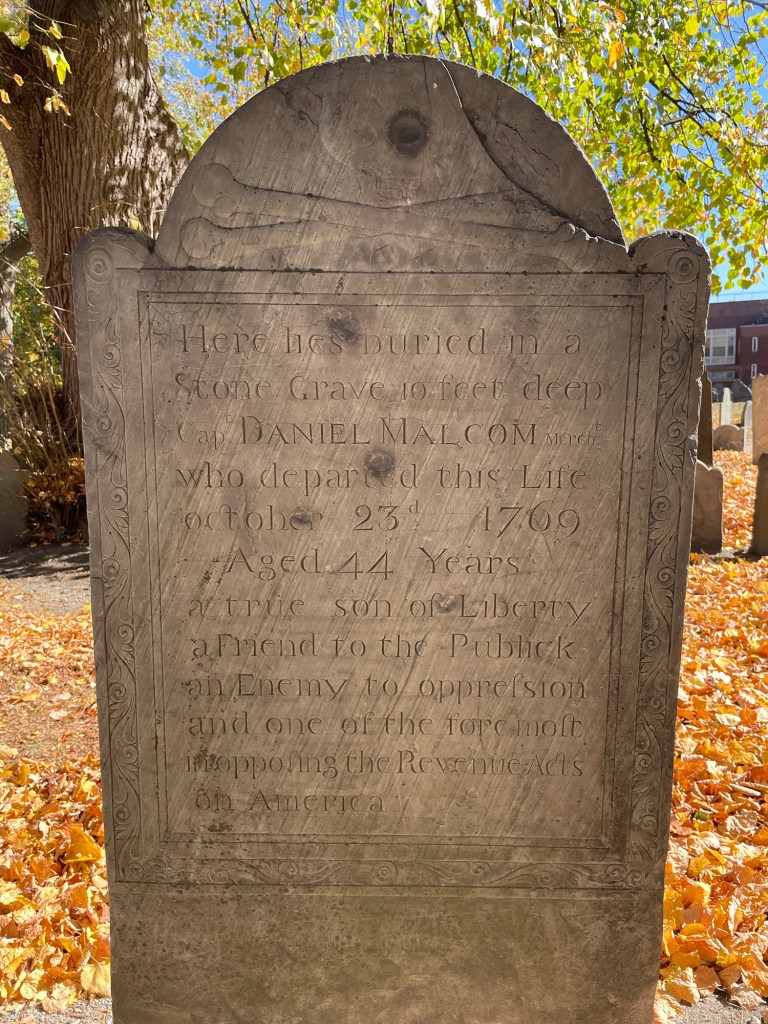

The cemetery is particularly known for its distinct slate gravestones, many adorned with intricate carvings that reflect the artistry of the era. Over the centuries, it has witnessed significant events, including the American Revolution, when it was used as a lookout point for British troops. During the Revolution, the burying ground’s prominent location overlooking the harbor gave it strategic military importance. At its southwest side the British established their North Battery and an earthworks from which they directed the shelling of Bunker Hill and ultimately the torching of Charlestown. Legend has it that British troops used gravestones for target practice. Many have interpreted the round scars on the gravestone of Captain Daniel Malcolm, an ardent son of liberty who spoke against Britain, as the result of musketballs shot at close range. The cemetery was used continually until the 1850s and is today, an evocative reminder of Boston’s early days, drawing visitors who seek to connect with the city’s storied history amidst its tranquil surroundings while the city stretches upwards around it. The cemetery is open and free to visit most of the year and is a great place to stroll and learn about Boston’s early history and see amazing stone carving!