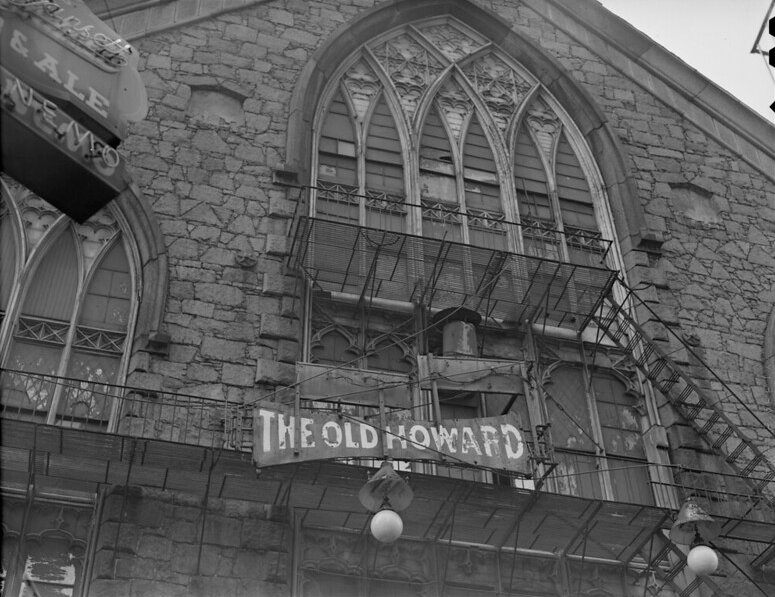

One of the more iconic theater buildings to ever stand in Boston was the Howard Athenaeum, later the Old Howard, which stood on the former Howard Street in Downtown Boston. The origins of the building begin in 1843, when a flimsy, tent was built to serve as a church for the small Millerite sect. The small but loyal congregation eventually abandoned the site following disappointment with the minister’s promise that the world would end in 1844. After Armageddon failed to materialize, the founder of the sect, William Miller, an ex-Deputy Sheriff from Poultney, Vermont, was discredited and the Millerites moved on. After running their former minister out of town, several church members (who had given up all their worldly possessions in preparation for their trip to heaven,) decided to recoup some of their losses by selling the property to Messers Boyd and Beard, who opened a theater here in 1845. A fire destroyed the structure, and it was replaced by a larger, fireproof building that same year. The new building was constructed in 1845 and was designed by architect Isaiah Rogers in the Gothic Revival style with massive granite blocks from Quincy.

The Howard Athenaeum saw many iconic performers and historical events in its 100 years. A young John Wilkes Booth, played Hamlet at the Howard before becoming famous for a more nefarious deed in Washington in 1865. Also, Sarah Parker Remond, a Black anti-slavery activist and lecturer with the American Anti-Slavery Society (and later a medical doctor), had bought a ticket through the mail for the Donizetti opera, Don Pasquale, but, upon arriving, refused to sit in a segregated section for the show. She was forcibly removed and pushed down a flight of stairs. She eventually won a desegregation lawsuit against the managers of the Howard Athenaeum and received $500 in a settlement.

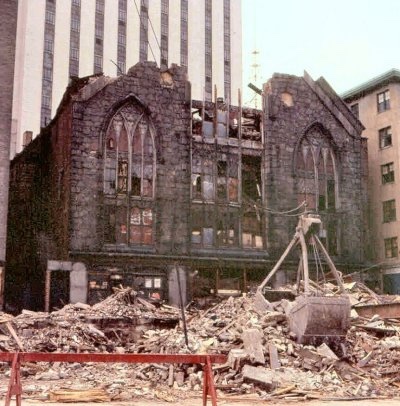

The theater was quickly deemed obsolete and second-tier compared to more modern theatres built nearby. By the mid-20th century, the Old Howard was largely featuring burlesque shows. To keep bringing in audiences, the burlesque performances got more risqué with each year. As a result, the Boston vice squad made the Old Howard the object of their attention. The Boston Vice squad made a 16 mm film during one of their raids in 1953 and captured on film the performance by “Irma the Body”. This film footage resulted in an indecency hearing which eventually led to the closing of the Old Howard in 1953. A fire a few years later along with Urban Renewal led to the demolition of the Old Howard by 1962. Like the former Suffolk Savings Bank (featured previously), the present Center Plaza Building is on the site.